The purpose of this article is to explain in clear, understandable terms exactly what widescreen is, how it affects the consumer, and how it works in the context of the home video environment. By necessity, this article is aimed more at the novice home theatre user than the dedicated enthusiast, but more advanced readers may wish to read it anyway as a refresher.

The first thing one has to understand about widescreen transfers is that feature films are almost always wider than standard television screens. That is, the aspect ratio of the film (the ratio between the width and the height of the picture) is wider than a standard TV's width.

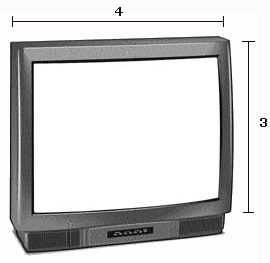

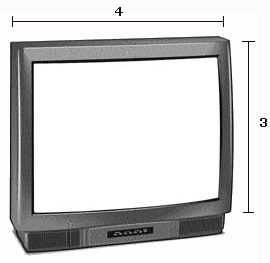

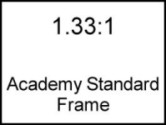

If you were to measure a TV screen, you'd note that the width of the screen is 1.33 times the height of the screen. In other words, a standard TV's aspect ratio is 1.33:1. This can also be expressed as an aspect ratio of 4:3, or four units wide by three units high.

From the beginning of cinema to the middle of the twentieth century, films were projected in this same ratio, which is why America's National Television Standards Committee defined the shape of the television screen this way in the 1950s. One slight problem resulted from this, however. The fact that there was little perceived difference between television and theatre saw theatre attendance in a state of decline, because audiences figured that there was no point in going to the theatre and paying to see something that they could watch for free in the comfort of their homes. Numerous ideas were proposed to win audiences back to the theatres, ranging from the short-lived idea of three dimensional projection to the recent IMAX exhibitions (which are quite a cut above any documentary you'll see on television). The two ideas that have stood the test of time are multi-channel audio and widescreen projection, which is the one we'll be concerning ourselves with during this series of articles.

Although any aspect ratio you care to imagine can be used in cinematography, there are two aspect ratios which are commonly used in modern films, and that we will discuss in detail here: 1.85:1 and 2.35:1, both of which are significantly wider than the ratio of a standard television set.

This is the original shape in

which movies were shown and the shape which was thus adopted by TV. This is the original shape in

which movies were shown and the shape which was thus adopted by TV. |

This is the shape adopted for

digital TV. This is the shape adopted for

digital TV. |

This is the narrower of the two

common shapes used for films today. This is the narrower of the two

common shapes used for films today. |

This is the wider of the two

common shapes used for films today. This is the wider of the two

common shapes used for films today. |

Films no longer fit on a television screen easily, a problem that has plagued home video since its very inception. There are two basic methods used to fit a wide image onto a narrow television screen, both of which involve compromises, advantages, and disadvantages. One involves modifying the shape of the image to fit the screen, which usually means a compromise in the content of the image.

This method is typically referred to as Panning & Scanning, and is a process in which an editor, not necessarily the same one who worked on the film, cuts out what they deem to be less important parts of the image in order to fit the resultant image fully onto a narrow television screen. While this method may look aesthetically pleasing to the less-educated eye, the results of this method severely damage the impact of the film, with numerous shots being made confusing or even nonsensical by this alteration. The wider the original aspect ratio of the film, the greater the impact of Panning & Scanning.

|

|

|

|

|

|

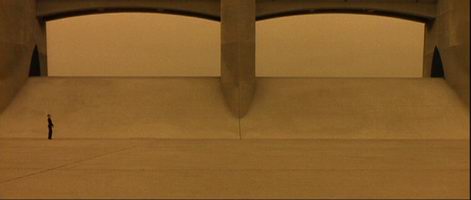

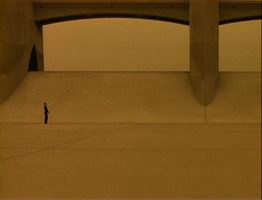

Both of the above examples come from the film Gattaca. Note the carefully composed widescreen shots on the left, emphasizing the smallness of the humans in relation to the enormous, carefully framed and symmetrical backgrounds. Both the scale and the symmetry of the backgrounds are destroyed by the panning & scanning process, decreasing the impact of these scenes. |

|

The other, much more preferable, method of making a wide image fit a narrow screen is to reduce the vertical height of the image so that it fits on the screen in its entirety. This method is called letterboxing, and its only drawback to the uninitiated is the necessary inclusion of black bars above and below the image. The advantage is that we are seeing the film in the aspect ratio that the director intended, rather than in an arbitrarily pared down version. This is a large part of the reason why televisions are being made wider. For now, here is a comparison table demonstrating what wide images look like when they are reduced in height in order to fit narrower television screens.

|

|

A 1.85:1 image, vertically shrunk in order to fit the 1.33:1 television screen. The entire image is preserved, with 28% of the original resolution lost. |

|

A 2.35:1 image, vertically shrunk in order to fit the 1.33:1 television screen. The entire image is preserved, with 43% of the original resolution lost. |

A 2.35:1 image, vertically shrunk in order to fit a 1.78:1 television screen. The entire image is preserved, and only 24% of the original resolution is lost. |

Now that you have been shown the difference between the wide image you see at the cinema and the narrow image shown on your TV set, with the resultant compromises to the original picture that this entails, we hope you'll have some understanding of why those "annoying black bars" are so important to home theatre. Rather than missing out on picture because of the "black bars", you are in fact gaining more picture.

Go on to Part 2

© Dean McIntosh (my bio sucks... read it anyway)

© Michael Demtschyna (read my bio)

February 2, 2002