A Widescreen Primer

a guide to widescreen on home video for those who can't define

"anamorphic"

Part Two - When is Less Actually More?

Introduction

If you have already read

Part One of this

article, you will be aware of the issues that arise when widescreen film is

transferred for viewing on narrower TVs. Compromises have to be made either to

the original width of the film or to the size of the image on the TV.

The compromise discussed in the preceding article was the Pan & Scan process, a

method by which the width of the widescreen image is sacrificed in order to fill

a narrow TV frame with the remainder of the image.

This is actually an oversimplification of the

issue, as there are two other compromise techniques

commonly used in filmmaking to accommodate the narrower aspect ratio of TVs -

soft matting (full frame transfers) of 1.85:1 movies, and Super 35 photography

of 2.35:1 movies. These are the subject of this

article. Additionally, we will also cover the concept of anamorphic photography,

used for the conventional production of 2.35:1 movies, as you need to understand

this to understand the requirement for Panning & Scanning in certain situations.

1.85:1 Movies can be Panned & Scanned or Open Matted

Pan & Scan

If the intended aspect ratio of a movie is

1.85:1, there are two ways in which the original widescreen image can be

modified for narrow TV screens. One of these is by using the Pan & Scan process

as already

discussed, but the more common process is known as open matting, or full frame

transfers. As a reminder, reproduced below is an example of a 1.85:1 movie that

has been Panned & Scanned.

Panning & Scanning a 1.85:1 film

This is a still frame from the 1998 classic Lock, Stock, And Two Smoking

Barrels. The film was originally presented in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1.

Note the bag of golf clubs on the extreme right of the frame near Frank Harper,

and the number of trees in the painting in the background. |

This is the same still frame from Lock, Stock, And Two Smoking Barrels

after having been cropped in order to fit onto a 1.33:1 television screen. The golf bag is

now missing, as are a noticeable number of trees on both sides of the background painting. The

result is a shot that looks and feels much more cramped than in its original form, and is not

what director Guy Ritchie had intended. |

Full Frame (Open Matte)

To fully understand the open matte or full frame

process (and the other processes mentioned later on), you need to realise that most film, all the way from original negative

to final theatrical release print, is actually 1.33:1 wide, regardless of the

final intended aspect ratio of the movie being shot or projected. Movie cameras

and film projectors both take 1.33:1 sized film.

When a 1.85:1 movie

is being shot, extra image is actually captured to that which the director and

cinematographer intend to be shown in the movie theatre. This is usually at the

top and the bottom of the image. When the image is being composed through the

camera, markings on the viewfinder show the director and cinematographer what will actually show up

theatrically, so that important image details are not left out of shot.

When it comes time to show the movie

theatrically, the 1.33:1 print has a masking plate placed in the image path so

that unwanted parts of the image are not shown in the theatre, and instead the

audience sees what the director intended. This process is known as soft

matting.

The key concept here is that there is indeed

extra image available to that which is shown theatrically, and to that

which was intended to be seen artistically by the director and the

cinematographer. This extra image comes in handy when it comes time to transfer

the movie to a TV format, as instead of losing image width, as with the Pan &

Scan process, you can simply remove the mattes to get a 1.33:1 image. Thus,

there is no loss of image, and indeed there is extra image shown.

However, all is not as rosy as it would

appear with this process, as two compromises have been made;

-

The image is no longer in the director and cinematographer's

intended aspect ratio. They composed their images to be seen at this aspect

ratio, and this is compromised by the full frame process, losing artistic

impact as a result.

-

Sometimes unwanted information can be seen in the opened

matte sections of the image, such as boom microphones, camera tracks, and

other things invisible at the theatrical aspect ratio.

A Full Frame Transfer of a 1.85:1 film

|

|

| This is a still frame from Forever

Young. This is how the movie appeared in theatres. |

This is the same still frame after the

top and bottom mattes have been removed. Note the extra picture shown at

the top and the bottom of the screen. Note also the different feel of

the images, with the additional information taking the focus away from

the intended subject of the shot. |

2.35:1 Films use Anamorphic Photography

As explained above, most film negative stock

is actually 1.33:1 wide, but this has been adapted to widescreen use. In the

case of 1.85:1 movies, a small amount of image resolution is sacrificed by

simply discarding the top and the bottom of the image. This is not a problem in

practice. However, for 2.35:1 movies, the situation is not as simple. If 2.35:1

movies were made simply by matting the top and the bottom of the image, 50% of

the resolution of the film stock would be lost. By the time this reached the

theatre, the nett result would be a very poor quality image.

This problem has been resolved by the

development of anamorphic photography. The processes involved have

various trade names, but the common ones are Panavison and Cinemascope.

In these processes, a special lens is placed

on the camera which distorts the image. It squeezes images horizontally

by a factor of 2 to 1. The entire film negative is used to capture the image.

The film negative is 1.33:1 wide, but the image captured is actually 2.35:1

wide. If you look at the developed negative, the image appears tall and narrow.

When the film is projected, a complementary lens is used to project the image

which expands the image back to the original 2.35:1. Thus, image quality is

maintained as no area of the negative is wasted.

Films produced using this process must be

Panned & Scanned when they are transferred to a narrow format. There is no

additional picture information available, as the entire camera negative has been

used up capturing the widescreen image.

2.35:1 Films can use the Super 35 Process

The Super 35 process is an attempt to achieve

much the same goals for 2.35:1 films as the open matte process achieves for

1.85:1 movies - an acceptable presentation of a widescreen movie on a narrow TV

screen.

A Super 35 image is photographed onto film

stock which is the same shape as ordinary 1.33:1 film stock, but where the space

normally reserved for audio tracks on the film stock is used for image.

The theatrical release print is made by

matting a little under 1/2 of the original negative and then zooming in on the remaining

image. For narrow TV images, again the image is opened up by removing the matte,

although the sides of the image are also narrowed a little in the process.

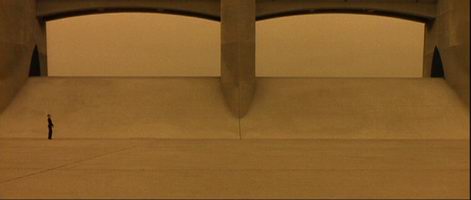

A Super 35 Transfer

|

|

|

This is a still from The Game, shot

using the Super 35 process. |

This is the full screen version of The Game.

Note the combination of image characteristics; firstly there is more

image top and bottom of screen, and secondly, there is less information

at the sides of the image. |

There are a number of issues inherent in

Super 35 cinematography and its open matte presentation. Firstly, since almost

half of the original negative image is discarded when producing the theatrical

print, the final resolution of the image is not as good as it would be with the

conventional anamorphic process used for the production of 2.35:1 movies. The

end result can be a very grainy looking theatrical image with poor image

resolution.

There are also issues with the open matte TV

presentation of the movie, more of an issue for special effects extravaganzas

than it is for more straightforward dramatic or comedic movies. Special effects

shots for movies are normally produced at a single aspect ratio, usually the

theatrical aspect ratio. So, special effects shots for 2.35:1 movies are

produced at 2.35:1 - to do otherwise would be a waste of resources and money for

what is already a very expensive process. When it comes time for these shots to

be prepared for display on narrow screens, unlike the conventional Super 35

shots which have additional image top and bottom which can be utilized, there is

no additional image available to show for the special effects shots, so they

need to be Panned & Scanned.

Closing Remarks

We hope that the above discussion of the

processes involved in producing narrow screen versions of widescreen movies will

serve to explain a number of things you may have noticed in your journey through

the widescreen wilderness, such as occasionally noticing less image on

your DVD than on VHS or TV versions of movies. Indeed, often the term

"widescreen presentation" may not be the most correct description for a

transfer, and "original theatrical aspect ratio" would be the more technically

accurate term.

Regardless of all of the above, hopefully we

have shown that these other presentation methods are merely compromises to

accommodate increasingly outdated and disappearing technology (narrow aspect

ratio display devices), and they all compromise the artistic integrity of the

director and cinematographer's vision. We should all be demanding transfers in

the original theatrical aspect ratio, as these are closest to the director's and

cinematographer's visions.

© Michael Demtschyna (read my bio)

March 24, 2005